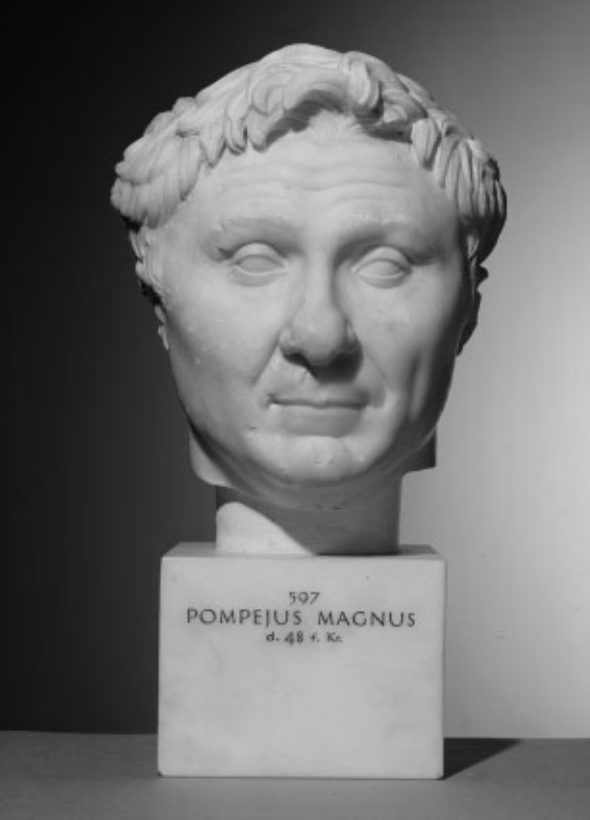

Gnaeus Pompeius (106-48 BCE, usually known in English as Pompey) served during the Social War under his father Cn. Pompeius Strabo (cos. 89 BCE) in Picenum and, after Strabo's sudden death in 87, he inherited his estates and connections there. When the Civil War started in 83, he raised three legions for SULLA, who then put him in charge of crushing resistance in Sicily and Africa. On his successful return he obliged Sulla to award him a TRIUMPH, although he had never held any magistracy. Sulla made a point of referring to Pompey as Magnus, “the Great,” as his soldiers used to do. The epithet soon became part of Pompey's name; his young age encouraged comparisons with Alexander.

Pompey acted as a free agent in the 70s, without holding any magistracy, relying only on his personal prestige and resources. After Sulla's death, the Senate was obliged to turn to him to assist in the suppression of Lepidus (78-77). He spent several years in Spain (77-71) where, besides making a decisive contribution to the demise of the alternative state created by SERTORIUS, he built a powerful network of support. His contribution to the repression of the slave revolt led by SPARTACUS in southern Italy (71) was less distinguished, although he played a crucial role in cornering the enemy; his attempt to obtain credit for the victory strained his relationship with CRASSUS, who had led the campaign. The two men, however, shared the consulship in 70, with Pompey skipping all the previous stages of the CURSUS HONORUM. It was a defining moment in late republican history, when many aspects of the Sullan settlement were undone: Pompey and Crassus themselves carried a law restoring the powers of the tribunes of the plebs, and a law carried by the praetor L. Aurelius Cotta ended the senatorial monopoly of jury membership. In 67, a law put forward by the tribune Gabinius assigned Pompey a three-year command against the pirates that operated in the eastern Mediterranean. His powers were wide-ranging and the mission was accomplished in a few months (see PIRACY). The echo of this success and the lack of progress of other Roman commanders in the region created the climate for the assignment of the command against Mithradates Eupator (lex Manilia, 66). Mithradates was soon defeated; he eventually committed suicide in 63. However, Pompey's mission did not end with this achievement: he completed the conquest of Asia Minor, created the new province of Bithynia-Pontos, and founded a number of cities. He continued his march into Syria, where he toppled the moribund Seleucid Dynasty and created a new province (see SYRIA (ROMAN AND BYZANTINE); SELEUCIDS); he also settled affairs in JUDAEA. The foundations for Rome's rule in the east were laid. Pompey's triumph in 61 was a formidable display of his might and prestige.

When Pompey returned to Italy in 62, his political position was of unprecedented significance. However, his request for land for his veterans and for the ratification of the decisions he had taken in the east found considerable opposition within the Senate. In 60, JULIUS CAESAR reconciled Pompey and Crassus and secured their support for his consulship in the following year. This partnership has become misleadingly known in modern scholarship as “First Triumvirate.” As consul Caesar pushed through two agrarian laws that provided for Pompey's veterans and secured the ratification of the eastern settlement; his reward was an extended command in Gaul and Illyricum. In 58/7, Pompey came under attack from CLODIUS PULCHER, but in 57 he received control of the grain supply of the city of Rome (cura annonae; see ANNONA) for five years. The alliance with Caesar and Crassus was renewed in 56, and as a result, in 55 Pompey was again joint consul with Crassus and received a five-year command of the Spanish provinces, which he governed through legates from Rome. In the same year he inaugurated the first stone theater ever built in Rome, a lasting sign of his wealth, influence, and boldness (see ROME, CITY OF: 2. REPUBLICAN; CAMPUS MARTIUS, REPUBLICAN).

After Crassus' death in 53, the tension with Caesar increased. The crisis that followed Clodius' death in 52 ended with Pompey's appointment as consul without a colleague, with the support of the Senate. Pompey styled himself as the champion of order, insisting that Caesar should give up his provinces before standing for the consulship. Caesar's refusal to do so, unless Pompey gave up his military commands in Italy and Spain too, made civil war inevitable. In January 49, Caesar left his province with his army and started a march towards Rome; Pompey, followed by hundreds of senators, sailed off to Greece, hoping that his forces in the east and his associates in Spain would soon create a stranglehold on Caesar's army. This did not happen. After dealing with the situation in Spain, Caesar crossed over to Greece in 48. After a first confrontation at Dyrrachium, the two armies met at PHARSALOS in Thessaly on August 9th. Despite having a larger contingent, Pompey was comprehensively defeated. He fled the battlefield and went into hiding, until he sought asylum with PTOLEMY XIII. The king sent him an encouraging reply, but had him murdered as soon as he landed in Egypt (September 28th). Pompey was an extraordinary individual. It would be rash to dismiss his qualities and merits in light of his final defeat. For about two decades, he was the most prominent man in Rome - truly a princeps. Although he ended his life fighting as the champion of the Senate, he was often regarded with suspicion by the nobility, and often posed as the friend of the people. His success was based on the understanding of the centrality of wealth and of the importance of building wide networks of support across Italy, the empire, and in client states. His legacy in provincial affairs was very significant.

The main contemporary sources for Pompey's age are the letters and speeches of Cicero, who had a complex political and personal relationship with him. PLUTARCH's biography is a valuable overview, partly influenced by lost contemporary sources, such as the work of THEOPHANES OF MYTILENE, an associate of Pompey.