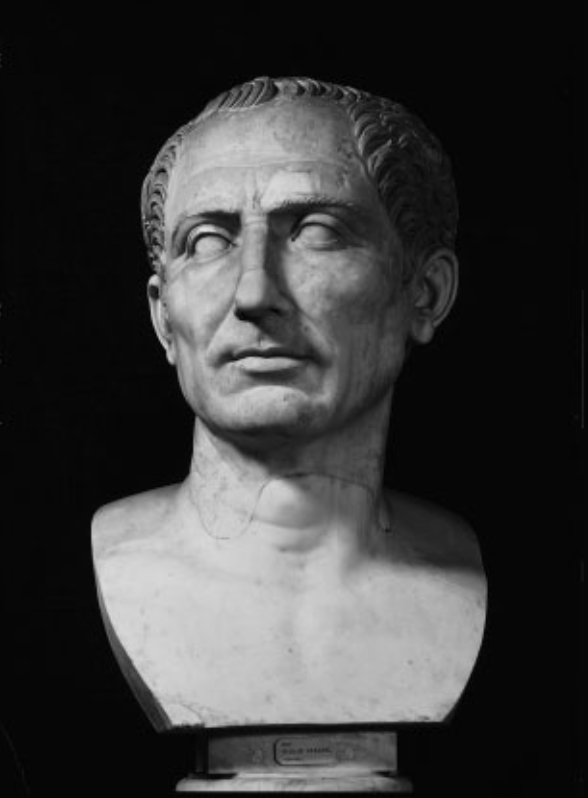

Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) was a politician, general, and writer who reached a unique position of supremacy in the last years of the Roman Republic. While historians continue to debate Caesar's role in bringing permanent monarchy to Rome, proponents and critics alike of autocracy and military conquest throughout history have recalled his name and deeds, making him an iconic figure in western culture.

BACKGROUND AND EARLY LIFE:

Caesar was born into the Iulii, an illustrious patrician family who claimed descent from the goddess VENUS and her son AENEAS, but one which had left little mark on history; Caesar's paternal aunt Julia had even been forced to marry the “new man” MARIUS, a connection that proved important as Marius' reputation soared (see PATRICIANS; HOMO NOVUS). During the civil war between Marius and SULLA that broke out in 88, Marius' associate Cinna married his daughter Cornelia to Caesar and selected him for the archaic priesthood of flamen dialis, a post Caesar lost upon Sulla's return to Italy and victory over the Marians in 82. At this time Caesar unexpectedly refused Sulla's invitation to end his marriage to Cornelia and come under Sulla's wing. Caesar's twenties were devoted to soldiering and the practice of oratory skills necessary to succeed in Roman politics. In 80, he joined the staff of Marcus Thermus, governor of Asia, under whom he won military distinction; sent on a mission to Bithynia, he formed a valuable relationship with its king, NIKOMEDES IV , later represented by his enemies as an amorous affair. Returning to Rome upon hearing of Sulla's death (78), he launched his oratorical career by bringing suit against several of the late dictator's associates; he then returned east, for further rhetorical study, during which time he again saw military activity - including capture of a band of pirates who had kidnapped him and held him to ransom. In 73, upon learning that he had been co-opted into the priestly college of the pontiffs - a sign that Caesar had made himself acceptable to the ruling establishment put in place by Sulla - he returned to Rome, where he was elected to a military tribunate, and then, for 69, a quaestorship, the first rung in the cursus honorum, which brought membership in the Senate (see PONTIFEX, PONTIFICES; CURSUS HONORUM, ROMAN). Shortly after his election to this office, Caesar's aunt Julia died, and Caesar took the chance to display effigies of Marius and Marius' son in her funeral procession, defying a prohibition by Sulla. Soon afterward, Cornelia also died, who was honored, like Julia, with a public oration by Caesar. The couple had one child, a daughter Julia, much beloved of Caesar.

POLITICAL CAREER:

Caesar spent his quaestorship - primarily a financial post - in the province of Further Spain, where some sources report that upon seeing a statue of Alexander the Great, he lamented his own failure yet to have accomplished memorable deeds. The story is apocryphal, but it underscores that Caesar was in many ways an ordinary Roman noble, who like anyone else, had to make his way through the cursus honorum. Caesar's chosen strategy, which proved successful even though it was novel for a patrician, was to seek popular favor; he continued to honor the memory of the people's hero Marius and attack policies of Sulla, and he also spent lavishly in the people's interests - even on what could be called bribes. The large debts thus incurred would have to be repaid through plunder seized in the provinces. En route back from Spain, Caesar stopped in the Latin colonies north of the Po River and expressed support for their desire for full Roman citizenship, laying the groundwork for a significant alliance. Back in Rome, he spoke on behalf of the laws granting POMPEY his commands against the pirates (in 67), and then King Mithradates (in 66; see MITHRADATIC WARS); Caesar also schemed with Pompey's great rival CRASSUS, who could help Caesar finan- cially. In 65, Caesar used his aedileship - a Senatorial post responsible for the upkeep of the city of Rome, its grain supply, and its festivals - to stage resplendent games, and to re-erect the trophies of Marius on the Capitoline Hill, to popular acclaim. Bribery helped clinch Caesar's surprising election to the post of pontifex maximus two years later (63) - after which conservative members of the Senate, including one of the defeated candidates, Catulus, turned on Caesar. Catulus tried to implicate Caesar in the conspiracy of Catiline later that year, but was not successful. Caesar's own effort, however, to persuade the senators to spare some of the conspirators also proved unsuccessful after a stirring speech by Cato the Younger, another of Caesar's conservative foes (see CATILINARIAN CONSPIRACY). At the start of his praetorship in 62, Caesar clashed further with Catulus and others, but temporary rapprochement followed. He then served as governor of Further Spain, where he fomented war to raise plunder - and win the vote of a TRIUMPH. Through the machinations of his opponents, this honor he was forced to waive, when he returned to Rome, in order to declare his candidacy for the consulship. Out of fear that he would be further stymied while in office, Caesar, in a master stroke, secretly brought together Pompey and Crassus in alliance with himself (forming the so-called “first triumvirate”). He then won a consulship for 59, along with Bibulus, a dim but fearless figure elected through a bribery fund subscribed to by Caesar's opponents. By every means, this faction tried to prevent Caesar, once in office, from passing a law which would grant land to veterans of Pompey's wars in the east. When it came time to vote, Caesar overwhelmed his colleague with violence, and Bibulus retreated to his house where he remained for the rest of the year, claiming that all public business transacted was illegal because he was watching the sky for omens. A second land law, helping indigent citizens, was also passed (as was a major revision of the regulations governing Rome's provincial governors). Amid all the controversy, relations between Caesar and Pompey deteriorated (Pompey did not like the opprobrium heaped on him by Bibulus and the others), but were patched up with the marriage of Pompey to Caesar's daughter Julia. At risk of being put on trial when he left office, Caesar obtained, through a law of the people, a five-year command over Rome's provinces in northern Italy and the Adriatic (Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum); to these was soon added the small territory Rome ruled in southern France, Transalpine Gaul. This command offered Caesar many advantages, beyond immunity from prosecution during its tenure. Should Caesar rack up military achievements, that could offset the controversial acts of his consulship and lead to a triumph; there would be ample scope for plundering; and he would have control of an army on the borders of Italy, and the ability to recruit in the rich countryside of Cisalpine Gaul, where he had his connections. And so at the start of 58, everything pointed to war. Caesar might have intended first to campaign against the Dacians of modern Romania, but when the HELVETII revived a plan to leave their homeland in what is modern Switzerland, he found his chance in Transalpine Gaul instead.

THE WAR IN GAUL:

PLUTARCH, in his life of Caesar, writes that the war in Gaul (58-51) marked a new beginning in Caesar's life, and in many ways this is correct. By the end of these campaigns, Caesar had a large, loyal, and well-trained army, with which he was able to invade Italy. He had won inordinate wealth, which he had used to recruit top officers and pay bribes back in Rome. And, above all, he had grown very used to giving orders, both orally and by written dispatches, and seeing those orders obeyed. At the same time, Caesar's achievements in Gaul were substantial and won him renown in Rome, not least because of the masterly dispatches he sent to the Senate, as well as his innovative commentaries - famously written in the third person (see GALLIC WAR (BELLUM GALLICUM )). Not only are these the chief source for the campaigns, they served permanently to redefine the large territory Caesar subdued, from the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean coast of modern France to the English Channel and the Rhine, as Gaul - while that which lay beyond Gaul became known as Germany. According to Caesar's account, after thwarting the planned migration of the Helvetii across Roman territory, he then was forced to wage war upon Rome's ally, Ariovistus, and expel the German leader's people from Gaul; he writes that trouble from other tribes forced him to fight again in 57 and 56, but all such trouble was the result of Rome's arrival in the area. With Gaul in principle subdued, he launched incursions across the Rhine and into Britain in 55 and 54. New resistance then developed back in Gaul, culminating in the great rising of 52 led by VERCINGETORIX, over whom Caesar prevailed after elaborate siege operations at the battle of ALESIA. The following year was spent finalizing pacification and administrative arrangements for the annexed territory, which despite the devastation wrought, developed into a rich and vital part of the Roman Empire. While in Gaul, Caesar had to keep up relations with helpers back in Rome, which he did through constant exchange of letters. By the start of 56, serious efforts were afoot to strip Caesar of his command, thwarted only when Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus reaffirmed their alliance at a meeting in Luca in northern Italy; Cicero, with whom Caesar throughout his life had a troubled relationship, was com- pelled to use his eloquence on behalf of Caesar before the Senate; and Caesar's command was renewed, while he was also voted fresh resources for the war (see CICERO, MARCUS TULLIUS). Pompey and Crassus were also given extended commands, in Spain and Syria, respectively. Pompey elected to stay in Italy and superintend affairs there, but relations with Caesar started to break down after the death of Julia (54) and as Pompey's jealousy for Caesar grew. Crassus, meanwhile, hoping to find prestige and plunder in war with the Parthians, was killed at CARRHAE (53). Political forces were realigning in Rome.

THE CIVIL WAR:

Caesar had, in 52, obtained a law granting him the right to stand for the consulship without having to enter the city of Rome (as he had been forced to in 60); his plan was to be elected to a second consulship in absentia, celebrate a triumph, and then (most likely) pass onto further campaigning. But as old enemies of Caesar and Pompey came together, Caesar's right to stand in absentia came into question. Though willing to negotiate, he made it clear that he would not give this up - probably not because he now feared successful prosecution, but to ensure celebration of the triumph he felt he deserved. Negotiations broke down. In January 49, two tribunes loyal to Caesar (one of them Marcus ANTONIUS) fled Rome, the consuls asked Pompey to take up an army, and Caesar with some of his troops crossed the RUBICON river that divided his province from Italy. With his characteristic lightning speed, he overran the peninsula. Pompey was forced to withdraw to the Balkans, but another of Caesar's foes, Domitius Ahenobarbus, stayed behind but was cut off with ten thousand men at Corfinium. Caesar spared the army and Ahenobarbus - showcasing a signature policy of clemency. He then went to Spain, to take over troops Pompey had raised there, returned to Italy, and finally crossed the Adriatic. The final showdown with Pompey was at the battle of PHARSALOS, where Caesar prevailed. Pompey's prestige was shattered, and he was subsequently killed while seeking refuge in Egypt. Pursuing Pompey there, Caesar became embroiled in a dispute over the Egyptian throne between Queen CLEOPATRA VII and her brother. Though later accounts may sensationalize, some kind of love affair ensued with Cleopatra, whom Caesar installed on the throne, and who gave birth to a son she named after Caesar (see PTOLEMY XV CAESAR). Caesar, meanwhile, traveled through Syria and Asia Minor, where he reorganized Rome's provincial administration, and then to Africa, where he finished off a lingering band of Pompeians and was named Dictator for a term of ten years (46). That title, along with other powers and honors granted with it, and lavish celebration of Caesar's victories (even over fellow citizens), suggested that a lasting autocracy was in store for Romans (see DICTATOR). Later, in 45, Caesar won a final victory in Spain over forces gathered there under Pompey's sons. After his return to Rome, even more extravagant decrees were passed in Caesar's honor, including a dictatorship for life - a totally unprecedented title - and distinctions typically reserved for gods (see RULER CULT, ROMAN).

FINAL DAYS AND ASSESSMENT:

During his final years, Caesar busily enacted reforms, including most famously a new solar calendar (see CALENDAR, ROMAN); he founded numerous colonies across the Mediterranean, to settle his soldiers and help the urban poor of Rome, and gave citizenship to Italians north of the Po; he formed great plans - for a codification of Roman law, for instance, and construction of a public library in Rome. He also was planning a major military campaign, in the east, on which he was to embark in 44. A number of Senators, meanwhile, including not just pardoned republicans such as Marcus Brutus but some of his own close associates (e.g., Trebonius), grew frustrated with Caesar's highhandedness and inaccessibility, the latter sure only to increase after Caesar left for the east. Never disposed to cultivating good relations with his senatorial colleagues, and ever more absorbed in making his plans and also in literary activity - including a pamphlet war over the memory of Cato, who had killed himself rather than accept Caesar's clemency - Caesar failed to win over this group through effective leadership. On March 15th (the “Ides” in the Roman calendar), a group of at least two dozen stabbed him to death beneath a statue of Pompey, at a meeting of the Senate. Modern biographers of Caesar, following Theodor MOMMSEN in his epic History of Rome, have tended to worship Caesar, seeing him as the most talented Roman of his generation or of all time, who understood the problems of the republic and made headway in solving them. Meanwhile, historians after Mommsen often tried to cut Caesar down to size. Caesar, they say, was typical of his time, an ordinary Roman noble, with no political vision; his assassination brought worse civil war, only put to rest by AUGUSTUS. For other critics still, Caesar himself was not so much blind to Rome's problems: he was the problem. On balance, one might conclude that Caesar, for all his talent, and for all that he did to help the people of Rome, Italy, and the provinces, was still too much a product of his class - the arrogant nobility of Rome - to grasp the necessity of persuading others to see things as he did. Caesar achieved a position of new suprem- acy, which set an important precedent, but his impatience made him ill-equipped to hold onto it and effect the lasting changes that Augustus, methodically, did.